The Paris Agreement 5 years on: big coal exporters like Australia face a reckoning

14 December 2020 | BY Jeremy Moss, UNSW | Ethics and Exports, Climate Justice Beyond the State

On Saturday, more than 70 global leaders came together at the UN’s Climate Ambition Summit, marking the fifth anniversary of the Paris Agreement.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison was denied a speaking slot, in recognition of Australia’s failure to set meaningful climate commitments. Meanwhile, the European Union and the UK committed to reduce domestic emissions by 55% and 68% respectively by 2030.

As welcome as these new commitments are, the Paris Agreement desperately needs to be updated. Since it was passed, the production and supply of fossil fuels for export has continued unabated. And the big exporters — such as Norway, Canada, the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia and of course Australia — take no responsibility for the emissions created when those fossil fuels are burned overseas.

It’s time this changed. Australia is the world’s biggest coal exporter. And in 2019, emissions from fossil fuels exported by this nation, as well as the US, Norway and Canada, accounted for more than 10% of total world emissions, according to calculations from a research project on Australia’s carbon budget at the University of NSW, which I run. Exporting nations are not legally responsible for these offshore emissions, but their actions are clearly at odds with the climate emergency.

Business as usual

A 2019 UN report notes governments are planning to extract 50% more fossil fuels than is consistent with meeting a 2℃ target and an alarming 120% more than a 1.5℃ target, by 2030. Coal is the main contributor to this supply overshoot.

But rather than reducing their production of fossil fuels, many countries are doubling down and actually increasing supply. For example, in Australia, government figures show the greenhouse gas emissions from Australia’s exported fossil fuels increased by 4.4% between 2018 to 2019.

Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter and approved three new fossil fuel projects in recent months: the Vickery coal mine extension, Olive Downs and the Narrabri Gas Project.

This is a worldwide trend. Let’s take Norway as another example. Norway gets the bulk of its electricity from hydropower and has partially divested its Government Pension Fund from some fossil fuels. Yet it’s also one of the largest exporters of greenhouse gases through its gas exports, behind Qatar and Russia.

The situation is mirrored in the corporate world. Many large fossil fuel companies are trumpeting their emissions reductions targets while continuing to push for new fossil fuel mining projects. BHP, one of the world’s biggest miners, stated it is reducing its emissions, yet in October the company increased its stake in an oil field in the Gulf of Mexico.

Responsibility doesn’t stop at the border

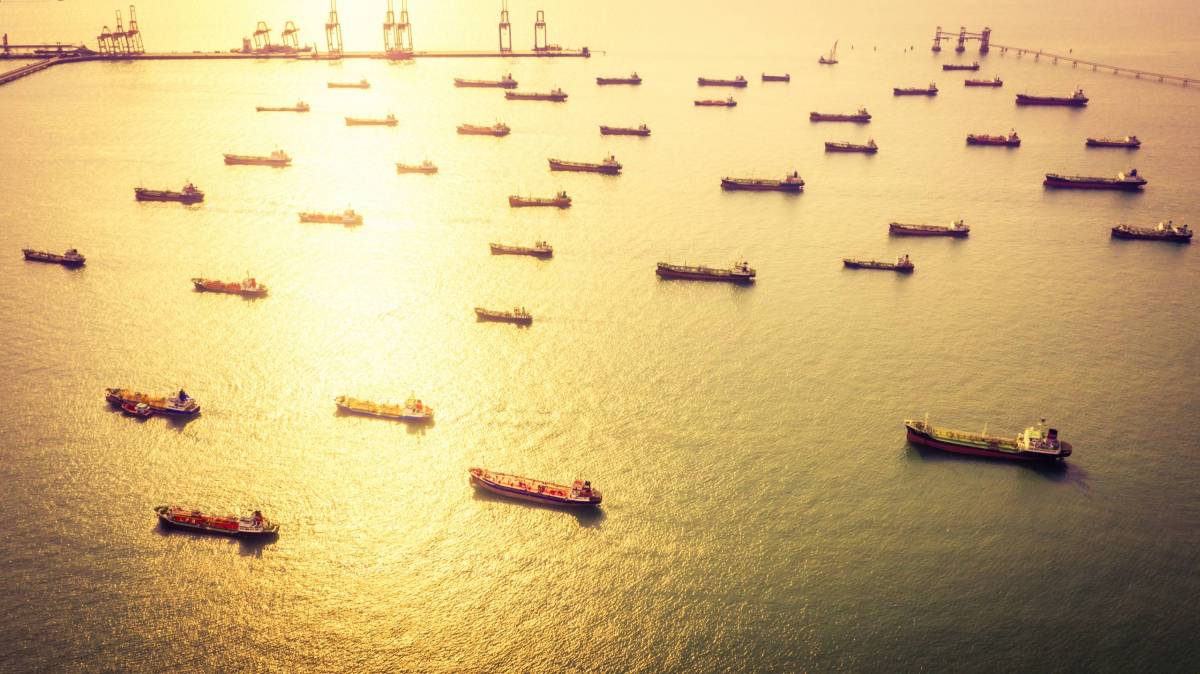

What underpins this situation is an outdated “territorial” model of responsibility for climate harms. Governments and companies seem to think responsibility stops at the border, not with the overall livability of the global climate. Once the coal, oil and gas products are loaded onto ships, they are no longer our problem.

Unfortunately, the accounting rules of the United Nations, under the Paris Agreement, currently allow exporters to pass on responsibility for fossil fuel emissions.

We must move from this territorial model of responsibility to one that considers the whole chain of responsibility for climate harms.

So what should Australia, Canada, the US, Norway and other exporting countries do to address the over-supply of fossil fuels?

First, they need to acknowledge their responsibility, at least in part, for the emissions and associated harms caused by their exports. Allowing compensation and funding for mitigation to track the role played in the causal chain better attributes responsibility and places mitigation burdens back on the exporting countries.

Future climate negotiations, such as in Glasgow in 2021 (COP26), need to adjust the scope of their targets to include robust reductions in the supply of fossil fuels in the next round of agreements.

Instead of just focusing on reducing demand, the process needs to function as a kind of “reverse OPEC” (the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), where exporting countries are given ambitious phase-out targets for their fossil fuel exports.

Drastic emissions cuts needed

The 2020 Production Gap report notes global fossil fuel production will have to decrease by 6% a year between 2020-30 to meet a 1.5℃ target.

For Australia, this must mean we include the reduction in “exported emissions” as part of any net-zero target. Australia’s exported emissions are double our domestic emissions – a situation that cannot continue.

Top of the list of what’s needed, is the phasing out of generous subsidies for fossil fuel producers. The billions of dollars currently spent annually in Australia on subsidising and encouraging fossil fuel exports are simply not compatible with the aims and spirit of the Paris Agreement.

Phasing out the supply of fossil fuels also needs to occur in a way that doesn’t just pay the current big suppliers to stop. Governments implementing a transition ought to think very carefully about how to fairly deploy scarce resources to ensure a just transition.

Last but not least, governments need to accept that the strong influence fossil fuel corporations wield over the political process is hindering global efforts to address climate change. The donations, rotation of industry staff to government positions and influence of fossil fuel lobby groups cannot lead to good decisions for the climate.

Placing a ban on such influence, particularly at future climate negotiations, would go a long way towards addressing the undue influence of the fossil fuel industry.

Until the fossil fuel export industry is subject to demanding targets, and made to accept responsibility for the emissions associated with their products, Earth will continue on its highly dangerous global warming trajectory.

–

This article originally appeared in The Conversation