Australia’s overseas climate aid needs to increase

8 November 2023 |

‘If you break it, fix it’– Australia’s obligation to take responsibility for climate harm in our region

High on the list of issues at this week’s Pacific Islands Forum in the Cook Islands will be responding to climate change and whether Australia is doing our fair share to support our Pacific neighbours.

On the evidence, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Australia is falling short of its obligations to assist developing countries to respond to climate change. Overwhelmingly, the harms of climate change are affecting developing countries, yet they have contributed least to the causes of climate change.

Even worse, as the 2022 United Nations Least Developed Countries report notes, while developing countries bear the least historical responsibility for climate harms, they are now bearing more of the burdens. During the last 50 years, 69% of worldwide deaths from climate disasters have occurred in these countries.

These facts will be top of mind for Pacific countries at the Forum, along with their knowledge that Australia’s climate transition plans are mainly focused on our own domestic emissions reductions and adaptation needs.

Currently, Australia spends six times as much on domestic action as it does on assisting developing countries with climate change.

Also, this international climate spending is not new and additional to general aid spending, but rather represents aid double-counted as climate finance for projects which have climate objectives.

This is a very poor response considering that Australia emits so much greenhouse gases.

In 2021, Australia’s reported domestic emissions were 488 Mts CO2-e, just over 1% of global emissions. That may not sound like much, but it places Australia as the world’s 16th largest emitter in gross terms. Countries like Australia have also been heavy emitters for many decades.

But the government does not count or take responsibility for the huge contribution to global emissions of being one of the world’s largest fossil fuel exporters. As we are only required to count GHG emissions created within Australia, the emissions associated with Australia’s exported fossil fuel products are not attributed to Australia.

This hides the significant fact that in 2021, emissions produced overseas from Australia’s fossil fuel exports were more than double our domestic emissions from all sources.

Given Australia’s significant contribution to climate change and unequal distribution of impacts internationally, the country needs a better roadmap for sharing responsibilities for strong climate action.

For example, Australia emits more than 10 times as many greenhouse gases as a country like PNG but it has among the lowest level of resources to deal with the impacts.

To meaningfully address their full climate impacts, countries like Australia need to consider the unequal distribution of climate harms, particularly for developing countries, when planning their climate responses, including by considering not only domestic ambitions, but what resources we can allocate to address these harms globally.

For instance, in the case where a company pollutes a river and accepts that it has wrongly caused a harm, it would be considered odd if it chose to only remediate damage to the small part of the river close by. The responsible course would be for the company to address the harms its pollution caused along the whole river, before it looked after its own interests. The same type of argument ought to apply to climate change.

What is the right split between Australia’s domestic and global actions? Currently the Australian government spends $6 in domestic climate action for every dollar spent overseas.

Estimates of the overall global cost of climate action for low-income countries vary greatly. Using the UN US$100 billion commitment to global climate finance as a guide, Australia’s resource allocation to this goal must come close to matching its domestic commitment. Some estimates put Australia’s fair share of the US $100 billion climate finance goal at AUD $4 billion per annum up until 2025.

A new report from Oxfam Australia argues that a fair share must include Australia’s liability from fossil fuel exports which would add another 25% to around AUD $5 billion per annum in new funding. This is the level required to adequately address Australia’s real and total contribution to climate change and focus on where the harms associated with its contribution actually occur.

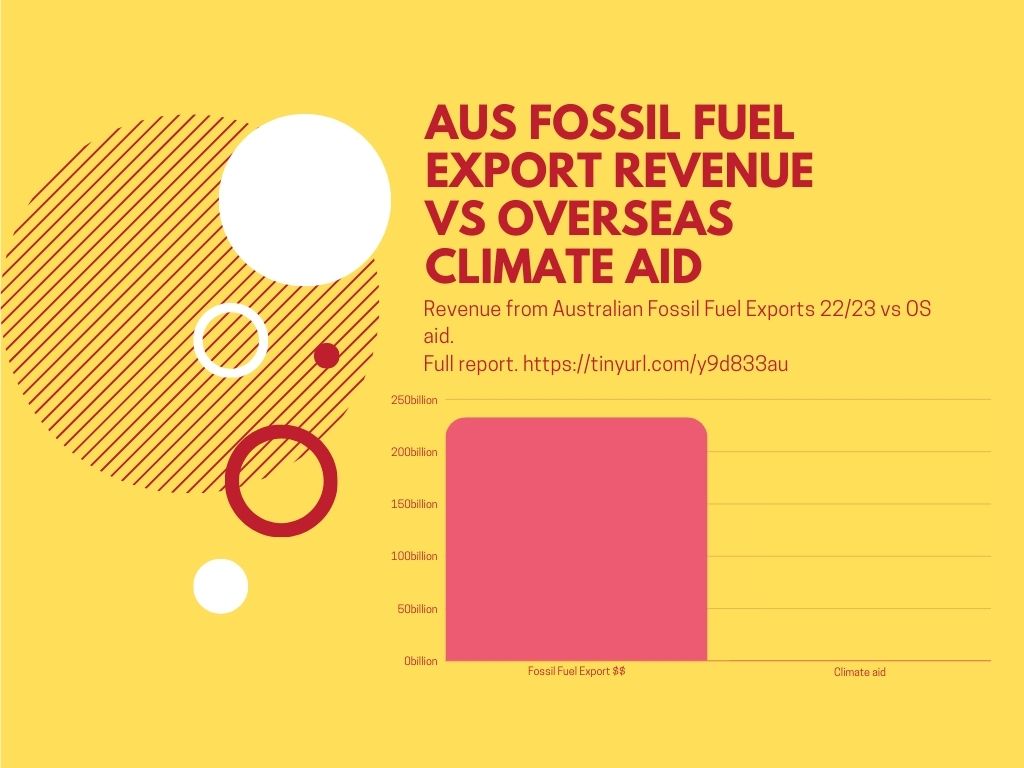

While significant, this is still less than half of Australia’s annual subsidies to the fossil fuel industry of AUD $11.1 billion. When we also consider the value of Australia’s fossil fuel exports in 2022–2023 alone was around AUD $233 billion dollars – 65 times the federal expenditure on meeting Australia’s net zero targets and more than 388 times the current annual amount spent on overseas climate aid, $5billion seems quite reasonable.

While the revenue from fossil fuels exports flows to private companies, relatively small additional taxes could raise amounts that are significant in this context, as many have argued.

If Australia is to act morally, it must acknowledge the full extent of its climate change contributions, including historical emissions, current domestic emissions and, crucially, emissions from fossil fuel exports. It must commit to allocating far greater resources to assisting developing countries to mitigate, adapt and compensate them for their climate losses.

Professor Jeremy Moss leads the Climate Justice Research program at UNSW and is the co-author of a new Oxfam report – If you break it, fix it: Australia’s global obligations for a just climate transition.